150mm APO Nikkor on 4x5 film

150mm APO Nikkor on 4x5 film

Here are some recommendations based on personal experience. This is by no means a complete survey.

Executive Summary: Most lenses for large format are quite good. For general shooting conditions, the images they make are often indistinguishable. Some of the best large format lenses are diffraction-limited: at their best settings they deliver the maximum resolution allowed by the laws of optics for their focal length. The advantages of one lens over another often boil down to secondary considerations like size, weight, filter size and price.

Note to Readers: As of 2020, I no longer own or use any of the equipment mentioned below but I hope you find this reference helpful.

Large Format lenses were made since the beginning of photography but in recent years the big four manufacturers were Schneider, Rodenstock, Fuji and Nikon. In most popular focal lengths we can find lenses of similar description from each of these manufacturers. They're all very good and in most cases only a trained eye or rigorous tester can distinguish differences between the images they make.

Note: although Schneider lenses are superb, be advised that some samples develop a condition known as Schneideritis, where black paint flecks off the walls of the lens elements and appears as spots.

Because Large Format lenses were manufactured over a long period of time, models and brands still circulate in the used market that were made by illustrious design houses of yore: Kodak, Zeiss, Goerz, Wollensak, Cooke, Voigtlander, Bausch and Lomb, Dallmeyer, Ilex, Meyer, Pinkham and Smith, etc. These "vintage" designs are still in use today. In some cases, they perform so well that except at extreme enlargements, no difference can be discerned. However for certain applications - portraits for example - some older lenses with optical imperfections are preferred, even sought out.

With regard to resolution, many modern lenses for Large Format do not offer dramatic improvements in sharpness over earlier versions: what they offer is greater coverage and reduced flare. Starting in the 1940's, manufacturers started coating lenses to minimize internal reflections which cause flare and loss of contrast. Coatings made possible lenses of complex design with many internal elements. Without effective coating and special optical glass, modern lens designs would be useless. Vintage lenses were purposely simple with a minimum of air/glass surfaces to avoid flare and reduce size and weight.

If we use a good lens shade, avoid harsh lighting and subjects which require extreme view camera movements, images made with vintage lenses can be virtually indistinguishable from those made with new gear. See this comparison of a 1990's era Nikkor 200mm M with two Bausch and Lomb 8x10 Protar Series V from the 1930's and this article which compares a 1950's era Schneider 90mm Angulon with a circa 2000 Schneider Super Symmar 110mm XL.

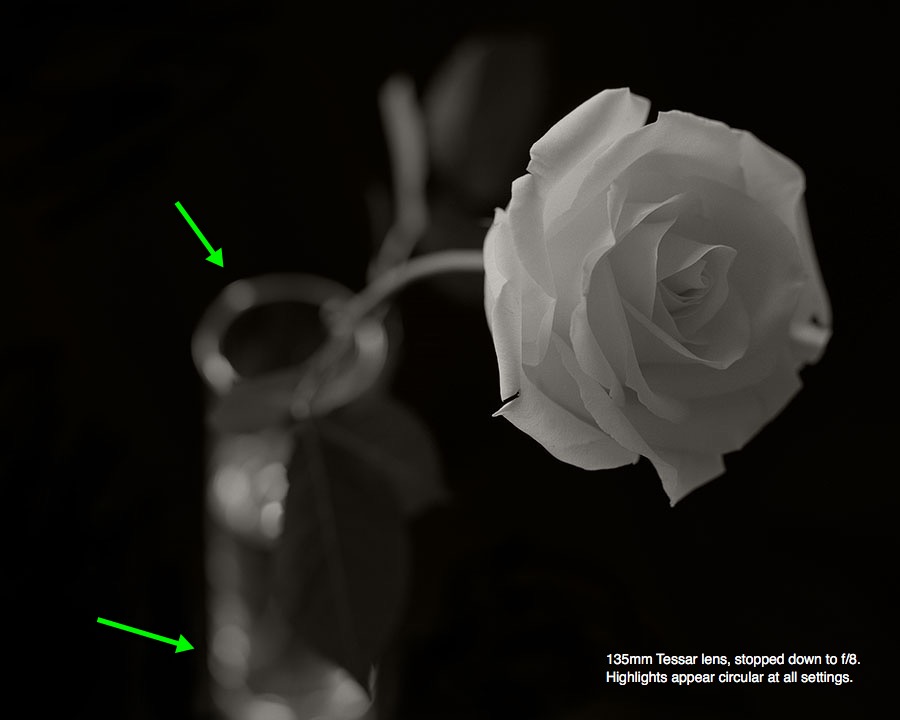

Vintage lenses have many-bladed irises, effectively round at all settings. This actually makes them superior for certain applications. Click here for further discussion.

Large Format lenses illuminate a very wide circle: not only larger than a typical digital sensor, larger than the typical digital camera ! When a lens produces a giant image, the interior of the camera is flooded with light, resulting in lens flare which degrades mage quality.

Large Format images require only modest enlargement. On the other hand, lenses designed for digital photography only need to illuminate a comparatively tiny sensor. Significant enlargement is required and the sensor is often recessed within the camera, making view camera movements impossible.

If we're shooting a modern digital camera with a high-resolution sensor, there is no advantage to using Large Format lenses - even if we can figure out how to mount the lens. Therefore the answer is... No.

Yes, definitely. See Made with a 5x7 view camera and Ilford FP4 film ?

Also see Adapted Lenses For Mirrorless Cameras for sample images made with a 35-105mm Zoom Nikkor Macro, 75mm Color-Heliar f/2.5, 135mm f/3.5 Nikkor AI-S and other manual focus classics. Like the best Large Format optics, these small manual focus lenses are very sharp and give excellent blur rendition. Many designs exist: these are only a few. Such lenses can be found "on the cheap".

General purpose lenses are good for photographs of landscape, architecture* and miscellaneous subjects at moderate to long distance. For these applications we value lenses of excellent sharpness with a wide circle of coverage. When we're shooting in the field - walking or trekking with our equipment - we appreciate lenses of compact size and low weight. Here are a few lenses which meet that description:

The Fujinon A series of lenses represents an innovative compromise in lens design. Like their plasmat cousins (Sironar, Symmar, etc) they provide excellent correction and wide coverage. Unlike standard plasmats which open to f/5.6, the Fujinon A series only open to a maximum aperture of f/9, a modification which makes them considerably smaller in size and weight and allows them to take smaller filters. While standard plasmats are corrected for distance-shooting at a ratio of 1:10, 1:20 etc. Fujinon A lenses are corrected for slightly closer work, more like 1:5. This "intermediate" correction makes them well suited for both Macro and Landscape photography.

The

Fujinon 240 A weighs only 245 grams and takes 52mm filters, yet it has a 336 mm circle of coverage: enough to function as a portrait lens on 4x5, a normal lens for 5x7, a wide-angle for 8x10 and an excellent close-up lens for all 3. This lens is so small, it's a delight to carry into the field and is ideal for

portraits in 4x5. It does nicely for 4x5 landscape too.

This 4x5 photo was taken with a Fujinon 240 lens. In the 12x15 print, you can clearly see details in the legs and wings of the fly on the lower right.

The

Fujinon 240 A weighs only 245 grams and takes 52mm filters, yet it has a 336 mm circle of coverage: enough to function as a portrait lens on 4x5, a normal lens for 5x7, a wide-angle for 8x10 and an excellent close-up lens for all 3. This lens is so small, it's a delight to carry into the field and is ideal for

portraits in 4x5. It does nicely for 4x5 landscape too.

This 4x5 photo was taken with a Fujinon 240 lens. In the 12x15 print, you can clearly see details in the legs and wings of the fly on the lower right.

Like the others in the A series, the

Fujinon 300 A is remarkably small and light, considering its performance. It has a generous 420 mm circle of coverage, takes 55 mm filters and weighs only 410 grams: much less than comparable lenses for the 8x10 format, for which it serves as a

normal lens. 300 mm is my favorite focal length for 5x7, equivalent to a 200 mm lens on 4x5.

Like the others in the A series, the

Fujinon 300 A is remarkably small and light, considering its performance. It has a generous 420 mm circle of coverage, takes 55 mm filters and weighs only 410 grams: much less than comparable lenses for the 8x10 format, for which it serves as a

normal lens. 300 mm is my favorite focal length for 5x7, equivalent to a 200 mm lens on 4x5.

Because of its wide circle of coverage, when used on 4x5 or 5x7 cameras, the 300 A can function as a wonderful longer lens for portraits and gives tremendous accommodation for view camera movements. It is also superb lens when used close-up on any format. This 4x5 image was taken with the 300A, with a lot of rise. A small section from the top shows plenty of detail, way off-center. This portrait was made on 5x7 film. The 300 A was discontinued by Fuji, but you can see it listed in this 1981 catalog.

The

200mm Nikkor M is a wonderful general-purpose lens for use in the field. it's very small and weighs only 180 grams - but it's razor sharp. It comes in a Copal 0 shutter and takes 52mm filters. Unlike longer lenses for 4x5, it renders images with only a slight sense of compression and distance.

The

200mm Nikkor M is a wonderful general-purpose lens for use in the field. it's very small and weighs only 180 grams - but it's razor sharp. It comes in a Copal 0 shutter and takes 52mm filters. Unlike longer lenses for 4x5, it renders images with only a slight sense of compression and distance.

(Lenses don't create perspective or flatness: subject distance does. With shorter lenses, we need to move in closer to the subject. If we move in too close, we get a distorted "stretched-out" effect known as foreshortening. If we step back too far, the subject looks compressed. At close range, the distance between a horse's eyes and nose is substantial, but from a great distance, it's rather small. There's a reason why the most popular focal lengths for portraits are of moderate length: they give a look which is least contrived and distracting: neither foreshortened not compressed. Here are some pictures made with a Nikkor 200M lens on 4x5 film. On 5x7, a 300mm lens (12-inch) gives the same basic perspective).

The Nikkor M series are Tessar designs: they are very sharp but have less coverage compared to "standard" Plasmat designs such as Sironar, Symmar, etc. On the other hand, they are small in comparison. Nikon says their M lenses are APO (highly color-corrected) at infinity but I have found that Tessars work very nicely at moderate and close distances too. Except when shooting at genuine macro distance like 1:1 and beyond, these lenses are excellent.

* For photographs of architectural interiors and facades we often need lenses which provide extra-wide coverage to facilitate extreme view camera movements. Fuji and Nikon lenses for these purposes generally have the name "Wide" or "W". The Schneider Super-Angulon and Rodenstock Grandagons designs fall into this category.

The

Rodenstock APO-Sironar-S lenses are superb. They are very sharp, have excellent control of flare and have lovely blur rendition. The MTF charts for this line of lenses is impressive: click here to see the Rodenstock lens catalog. Note that most lenses in this category give their best performance at f/16 and f/22.

The

Rodenstock APO-Sironar-S lenses are superb. They are very sharp, have excellent control of flare and have lovely blur rendition. The MTF charts for this line of lenses is impressive: click here to see the Rodenstock lens catalog. Note that most lenses in this category give their best performance at f/16 and f/22.

This 4x5 image was made with a 150mm Rodenstock APO-Sironar-S lens. The tonality and detail is...delicious. As you can see from the detail section, this lens is quite sharp. It weighs only 230 grams and takes tiny 49 mm filters. Yet it covers 231 mm - enough to for 5x7 as a wide lens and plenty for 4x5 as a normal lens. Here are some pictures made with a 150mm APO Sironar-S. Sironar-S lenses are corrected for 1:10, which makes them fine performers at all but macro distance.

The

Fujinon 450C is a compact lens with long reach and tremendous coverage. Mounted in a Copal #1 shutter, it weighs only 270 grams, takes 52 mm filters, yet covers 486 mm, enough for the 11x14 format. It makes a nice

portrait lens for 8x10, a long lens for 5x7 and it's a very long lens for 4x5, but it's smaller and lighter than most lenses. The 300C is another in the same family: C stands for Compact !

The

Fujinon 450C is a compact lens with long reach and tremendous coverage. Mounted in a Copal #1 shutter, it weighs only 270 grams, takes 52 mm filters, yet covers 486 mm, enough for the 11x14 format. It makes a nice

portrait lens for 8x10, a long lens for 5x7 and it's a very long lens for 4x5, but it's smaller and lighter than most lenses. The 300C is another in the same family: C stands for Compact !

This image was made on 8x10 with a 450C. It tells the whole story.

The

Fujinon 400T is a

telephoto lens for 4x5: even though it gives a 400 mm effect, it requires only 250 mm of bellows draw. It works great on cameras like the Tachihara wooden field camera - which is otherwise limited to 300 mm lenses of "normal" design. Mounted in a Copal #1 shutter, it takes 67 mm filters and weighs 700 grams.

The

Fujinon 400T is a

telephoto lens for 4x5: even though it gives a 400 mm effect, it requires only 250 mm of bellows draw. It works great on cameras like the Tachihara wooden field camera - which is otherwise limited to 300 mm lenses of "normal" design. Mounted in a Copal #1 shutter, it takes 67 mm filters and weighs 700 grams.

This 4x5 image was made with the 400T, at a great distance from the subject. Note the detail section of the negative. Here is another one taken with this lens: sharp as a tack. If you want a long lens for 4x5, but your camera has limited bellows extension, then telephoto lenses are a great option. Fujinon is not the only brand.

Notice the diaphragm in this vintage Heliar lens and how many leaves it has: 18 ? The aperture is basically circular at all settings and the blades are curved, not straight. This helps retain lovely out of focus rendering - something overlooked in modern lenses which have only 5, 6, or sometimes 8 blades. With the revival of interest in beautiful blur rendition, new lenses are finally being designed with 9 or more curved blades.

Notice the diaphragm in this vintage Heliar lens and how many leaves it has: 18 ? The aperture is basically circular at all settings and the blades are curved, not straight. This helps retain lovely out of focus rendering - something overlooked in modern lenses which have only 5, 6, or sometimes 8 blades. With the revival of interest in beautiful blur rendition, new lenses are finally being designed with 9 or more curved blades.

When everything in an image is in focus, diaphragm shape doesn't matter. For portraits and close work where blurry points of light appear in the image, having a truly round diaphragm can make a substantial difference. You can see an example portrait here and example photographs of flowers here and here.

If you plan to make photos with specular highlights and you prefer truly round artifacts, find an older lens with a round diaphragm. If it's in an old shutter you can use it as is, provided the shutter is in good shape. If not, you can get a barrel-mounted lens and use either a Sinar Copal Shutter (see below) or have it mounted in an old shutter (see below).

Portrait lenses - also known as "Soft Focus" lenses - are designed to produce images with conspicuous aberrations: blur, glow, diffusion, halos, etc. These lenses were popular in years past because they soften imperfections in the skin and render the subject with a pleasant ethereal quality.

Jim Galli and others on the Large Format Photography Forum have done extensive shooting with vintage portrait lenses, some of which go back to the 1800's (read discussion here.) Many of these lenses allow you to control the "softness" by rotating a dial which moves one lens element relative to the another.

Portrait lenses - also known as "Soft Focus" lenses - are designed to produce images with conspicuous aberrations: blur, glow, diffusion, halos, etc. These lenses were popular in years past because they soften imperfections in the skin and render the subject with a pleasant ethereal quality.

Jim Galli and others on the Large Format Photography Forum have done extensive shooting with vintage portrait lenses, some of which go back to the 1800's (read discussion here.) Many of these lenses allow you to control the "softness" by rotating a dial which moves one lens element relative to the another.

Here is a set of photos I made using a very old and very rare 9 inch Kershaw Soft Focus lens, provided by portrait photographer Eddie Gunks. The Kershaw produces a strong halo effect which can be quite beautiful. One method of determining the ideal portrait length for lenses, is to simply add the length and width of the film edges. On 4x5 film, 4 + 5 = 9 inches or 225mm.

Reinhold Schnable has re-introduced the Wollaston Meniscus lens, one of the earliest designs of all. it's a superb lens for "pictorial" effects and comes with a set of perfectly round apertures. He makes them in a variety of focal lengths and configurations.

There are also modern portrait lenses, such as the Cooke Portrait PS945, (no longer) manufactured by Cooke, a venerable name in the world of still and cinema optics. The Rodenstock Imagon and Fujinon SF are no longer made and give similar results - but every portrait lens has its own "personality". With these modern designs, uncorrected aberrations diminish as you stop down the lens, so you can control the effects by your choice of aperture. Stopped down sufficiently, they behave like ordinary lenses: razor sharp. The Imagon and the Fujinon SF also come with special filters which modify the look and shape of highlights and halos. To read a copy of the instruction manual for the Fujinon SFS lenses, click here.

There are also modern portrait lenses, such as the Cooke Portrait PS945, (no longer) manufactured by Cooke, a venerable name in the world of still and cinema optics. The Rodenstock Imagon and Fujinon SF are no longer made and give similar results - but every portrait lens has its own "personality". With these modern designs, uncorrected aberrations diminish as you stop down the lens, so you can control the effects by your choice of aperture. Stopped down sufficiently, they behave like ordinary lenses: razor sharp. The Imagon and the Fujinon SF also come with special filters which modify the look and shape of highlights and halos. To read a copy of the instruction manual for the Fujinon SFS lenses, click here.

Not everyone is fond of the full diffusion effect. To some, it looks contrived and distracting. However, when opened to just the right aperture, these lenses provide a sublime blur rendition and a very mild "soft focus" effect. Here are some photos made with a 180mm Fujinon SF lens, a 3-element design. Stopped down a bit, it shows just a trace of the special "portrait" effect in the highlights and the overall blur rendition is only slightly exaggerated.

Normal lenses for landscapes and portraits (like the ones above) are optimized for shooting at an average distance, at a ratio of 1:10 or more. For very close work however, normal lenses do not perform at their best, particularly as we reach out towards the edges of lens coverage. Once we focus close to 1:1 and beyond, macro lenses come into their own.

Macro lenses are designed for shooting in ratios of at 1:1 and closer. Like other modern lenses, macros have a complex design: many elements, several groups. They are similar to general-purpose lenses but have different internal designs optimized for very close shooting. They produce a wide image circle, enabling full use of view-camera movements for control of perspective and depth of field. The Rodenstock APO Macro Sironar, Schneider Macro-Symmar HM and Nikon Macro Nikkor-AM (ED) lenses fall into this category.

Macro lenses are designed for shooting in ratios of at 1:1 and closer. Like other modern lenses, macros have a complex design: many elements, several groups. They are similar to general-purpose lenses but have different internal designs optimized for very close shooting. They produce a wide image circle, enabling full use of view-camera movements for control of perspective and depth of field. The Rodenstock APO Macro Sironar, Schneider Macro-Symmar HM and Nikon Macro Nikkor-AM (ED) lenses fall into this category.

Most Macro lenses open to f/5.6, which makes it easy to view the subject and achieve precise focus at close distances, even under poor lighting. They usually come mounted in a shutter or a Sinar DB lens board. This photo was made with a 210mm Rodenstock Macro Sironar N, at around 2:1 magnification. Here is a gallery of photographs made with that lens.

Are macro lenses absolutely necessary ? No, especially if we shoot in black and white or make prints at only moderate enlargement. Many non-macro lenses perform well at close distance and many macro lenses perform well at infinity. The difference between normal and macro lens performance becomes noticeable at higher magnification and larger print size. Therefore, testing is the most reliable way to find out if a lens meets your specific requirements.

Process lenses are designed to make high-quality color separation and copy negatives in "process" cameras for the photo engraving industry. They are optimized for shooting flat surfaces at 1:1 magnification and are apochromatic, giving identical focus and image size to red, green and blue light. They are often available in barrel - without a shutter - and are thus priced lower than other lenses of comparable focal length. They don't have a lot of extra coverage, but they are very sharp and their images have very low distortion.

Process lenses are designed to make high-quality color separation and copy negatives in "process" cameras for the photo engraving industry. They are optimized for shooting flat surfaces at 1:1 magnification and are apochromatic, giving identical focus and image size to red, green and blue light. They are often available in barrel - without a shutter - and are thus priced lower than other lenses of comparable focal length. They don't have a lot of extra coverage, but they are very sharp and their images have very low distortion.

The Goerz Apochromat-Artar, Schneider G-Claron, Nikon APO Nikkor and Rodenstock APO Ronar lenses fall into this category. They generally open to f/9 and are thus comparatively small and light. If you have a Sinar shutter, you can use them as-is. Some of them come in shutters and some people purchase them in-barrel and proceed to mount them into a shutter. Here's a photo made with a 150mm APO Nikkor lens. I mounted it on a simple cardboard lens board and used it with a Sinar Copal Shutter.

Their optics are rather simple: 4 or 6 elements in 2 groups, a symmetrical design, with modest coverage - which works very well when shooting straight ahead. This image was made with a 240mm APO Nikkor, at around 1:1 magnification. Because they open to f/9, they can be a little difficult to focus when working at a close distance in dim lighting. For other applications however, f/9 is plenty wide enough: this image was made outdoors, with a 360mm APO Nikkor, on 5x7 HP5+ film.

Here are some photos made with a 610mm APO Nikkor, on 4x5 TMY film.

Some very fine lenses are mounted "in barrel". They have have no shutter of their own: just a diaphragm. Many vintage and modern lenses are

available in barrel. Some are wonderful old portrait lenses. Others are modern process lenses taken from high-resolution engraving machines - like the APO Nikkor series, which are affordable, easy to find, small, light and razor sharp at all distances. Barrel-mounted lenses can save you money, size and weight.

Some very fine lenses are mounted "in barrel". They have have no shutter of their own: just a diaphragm. Many vintage and modern lenses are

available in barrel. Some are wonderful old portrait lenses. Others are modern process lenses taken from high-resolution engraving machines - like the APO Nikkor series, which are affordable, easy to find, small, light and razor sharp at all distances. Barrel-mounted lenses can save you money, size and weight.

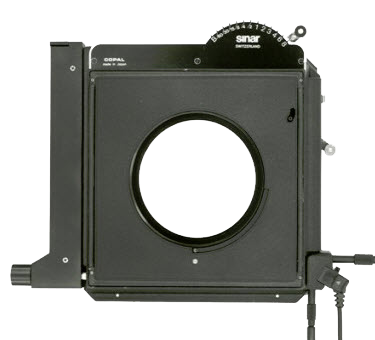

The Sinar Copal Shutter lets you shoot with vintage and barrel lenses. It fits onto the front standard of Sinar cameras, just behind the lens board. You set the shutter speed with the dial at the top. The Copal shutter is self-cocking and precise exposure times go from 1/60 to 8 seconds. Of course, you can still use lenses that are mounted in a standard shutter if you like: just leave the Sinar Shutter open.

Sinaron DB-Mounted lenses (like the one on the right) were made to work directly with the Sinar Shutter. You set the aperture, not on the lens, but on a large dial at the side of the shutter. With DB-mounted lenses, you can operate everything from behind the camera: there is no need to walk to the front to close or open anything. No need to cock the shutter, because it is self-cocking. You can preview depth of field by gently squeezing the cable release: Otherwise, the lens stays wide open for best focus and viewing. Pictured at right is a 210mm Sinaron DB, a Sinar-mounted 210mm Rodenstock Sironar-N lens. Sinar chose Rodenstock lenses for their Sinaron line, but you can mount any lens of reasonable size.

Sinaron DB-Mounted lenses (like the one on the right) were made to work directly with the Sinar Shutter. You set the aperture, not on the lens, but on a large dial at the side of the shutter. With DB-mounted lenses, you can operate everything from behind the camera: there is no need to walk to the front to close or open anything. No need to cock the shutter, because it is self-cocking. You can preview depth of field by gently squeezing the cable release: Otherwise, the lens stays wide open for best focus and viewing. Pictured at right is a 210mm Sinaron DB, a Sinar-mounted 210mm Rodenstock Sironar-N lens. Sinar chose Rodenstock lenses for their Sinaron line, but you can mount any lens of reasonable size.

Here is a gallery of photographs made with a 210mm Macro Sironar lens, mounted in a Sinar DB Shutter. Here are a few photos made with the Sinar Shutter and a 610mm APO Nikkor lens.

Front-mounting a lens in an Alphax or Betax Shutter is another attractive option: all you need is an adapter, which can be made by a machine shop. SK Grimes made a wonderful adapter for my 1950's Red Dot Apochromat Artar lens. The barrel-mounted lens fits into the front of the Alphax #4 shutter and can be replaced with another lens. Grimes made the adapter and it works perfectly.

Front-mounting a lens in an Alphax or Betax Shutter is another attractive option: all you need is an adapter, which can be made by a machine shop. SK Grimes made a wonderful adapter for my 1950's Red Dot Apochromat Artar lens. The barrel-mounted lens fits into the front of the Alphax #4 shutter and can be replaced with another lens. Grimes made the adapter and it works perfectly.

For a list of shutters and their sizes, see the SK Grimes site: USA sizes for US-made shutters like Ilex, Alphax, Betax and Metric sizes for Copal, Compur, Compound etc. For USA shutters, flange information is given as inches diameter and threads per inch. For example, the Alphax # 4 Shutter opening is 2.618 inches wide, and the threads are 30 per inch. For metric shutters, flange information is given in mm and threads are listed in millimeters per turn.

Normally, a shutter is positioned between the front and rear elements of a lens: the shutter mechanism provides both the shutter and the adjustable aperture or iris. When front-mounting, we place the entire lens in front of the shutter. If the lens has its own iris (as do barrel-mounted lenses), we get to keep it - which is usually a good thing since vintage barrel-mounted lenses have round apertures with many blades. The Artar has a 14-bladed iris, making it effectively round at all settings.

On the left you can see the Alphax #4 Shutter on the front of my vintage wooden 5x7 camera, a Kodak 2D. The Red Dot Apochromat Artar lens is screwed into the adapter. The Alphax shutter has speeds from 1/2 to 1/50 second, as well as B (bulb) and T (time exposure). On the right the same lens is mounted on my 4x5 Tachihara Field camera. Grimes made an adapter for the Alphax #4 shutter to a standard Technika board.

On the left you can see the Alphax #4 Shutter on the front of my vintage wooden 5x7 camera, a Kodak 2D. The Red Dot Apochromat Artar lens is screwed into the adapter. The Alphax shutter has speeds from 1/2 to 1/50 second, as well as B (bulb) and T (time exposure). On the right the same lens is mounted on my 4x5 Tachihara Field camera. Grimes made an adapter for the Alphax #4 shutter to a standard Technika board.

On 5x7 film masked to the 4:5 ratio a 10 3/4 inches (273mm) is an ideal "portrait" length, roughly equivalent to a classic 9 inch lens on 4x5 film. (The Cooke Portrait PS945 Lens mentioned above is a 9-inch lens.) Here is a gallery of photographs made on 5x7 film with a 10 3/4 inch Goerz Red Dot Apochromat Artar lens, mounted in an Alphax #4 Shutter.

Here is a photo that compares the bokeh or blur rendition of 4 different lenses of standard "portrait" length: 210mm Heliar, 210mm Tessar, 240mm Fujinon A, 240mm APO Nikkor. These lenses represent a sample of designs old and new. In this comparison, all the lenses are stopped down to f/11, and the contrast has been adjusted so that they all match.

Here is a photo that compares the bokeh or blur rendition of 4 different lenses of standard "portrait" length: 210mm Heliar, 210mm Tessar, 240mm Fujinon A, 240mm APO Nikkor. These lenses represent a sample of designs old and new. In this comparison, all the lenses are stopped down to f/11, and the contrast has been adjusted so that they all match.

Note: When I made the tests, I focused with the lenses wide open, then stopped them down to f/11 to make the exposure. The first image in the series (made with a 210mm Heliar) exhibits focus shift: the area of sharp focus moved slightly closer when the aperture was changed. As a result, distant objects appear more blurry but this is an accident. My sincere apologies.

After adjusting for minor variations in contrast (and focus shift), it is virtually impossible to see any difference whatsoever between the blur rendition of these lenses. Can you tell the difference ? At moderate degrees of enlargement, it's impossible to tell the difference between these lenses altogether. We are left with other, more practical considerations like coverage, size, weight, filter size, price, availability, etc.

Here is another photo which compares the bokeh or blur rendition of 3 different lenses of standard "normal" length: 150mm Heliar, 150mm APO Nikkor, 150mm APO Sironar-S. These lenses represent a variety of optical designs: 5-element Heliar, 4-element Dialyte, 6-element Plasmat. All the lenses are stopped down to f/11 and the contrast has been adjusted so that they all match. After adjusting for minor variations in contrast, it is very hard to see any difference between the image rendition of these lenses.

Here is another photo which compares the bokeh or blur rendition of 3 different lenses of standard "normal" length: 150mm Heliar, 150mm APO Nikkor, 150mm APO Sironar-S. These lenses represent a variety of optical designs: 5-element Heliar, 4-element Dialyte, 6-element Plasmat. All the lenses are stopped down to f/11 and the contrast has been adjusted so that they all match. After adjusting for minor variations in contrast, it is very hard to see any difference between the image rendition of these lenses.

A word to the wise: beware of articles where the author relies on subjective terms like creamy, biting, buttery, etc. The best way to compare the signature of different lenses is to shoot the same subject under identical lighting and examine the resulting images side-by-side. The differences, when present, are oft-times exaggerated, especially when shooting the lens stopped-down to typical apertures.

Note: These bokeh tests do not evaluate the rendering of sun-stars and specular highlights. Points of light take the shape of the lens aperture. These tests simulate typical scenes which do not contain bright spots, shot at typical aperture.

To get round highlights, shoot the lens wide open or use a lens with a truly circular aperture. For information about how lenses with circular aperture render specular highlights, see Vintage Lenses: ROUND Apertures above.

Here are some collections of photographs made with large format black and white film, using a variety of large format lenses, at different apertures and film sizes.

|

|

10 3/4 inch Apochromat Artar on 5x7 film

10 3/4 inch Apochromat Artar on 5x7 film